If you violated the 5/8" edge distance guidelines on the rear spar doubler when mating your wings, all is not lost! With a little patience, you can get a second chance with a new doubler.

This article, originally published in March 2007, will be of no value to 99 percent of you because, I'm guessing, 99 percent of RV airplane builders don't mess up the edge distance on the rear spar "fork" when mating the wings. To the other 1 percent, however, there's very little guidance on what to do. So perhaps this will help. Later in the article, I'll show you the "gotcha" that got me in trouble. Originally I thought my misdrilled bolt hole was the culprit. While that didn't help things, that wasn't the problem. But more on that later.

I have to thank Ken Scott at Van's, who gave me a lot of sympathy, and some encouragement, for my plight. After I discovered this mistake, I admit my confidence level took a significant hit. But Ken gave me every indication that working carefully, it could be fixed.

OK, so your edge distance is less than the 5/8" required by Van's. What should you do? Should you replace it all? As I indicated in an Editor's Page column, there was never any question for me. But you have to make that decision for yourself. I'm not an engineer and I did get some e-mail that suggested I was likely to cause more damage to the rear spar in dismantling the unit than I had compromised safety by leaving the edge distance slightly outside of tolerance. I didn't agree and Van's didn't agree, but you have to make that call for yourself, mindful that Van's says this callout -- the 5/8" edge distance -- is one of the few "sacred measurements" on the entire project.

If you're still reading -- and I guess you are -- you've decided to replace it. What I'm about to describe is "my" method. My method involves doing whatever it takes to get things right. No shortcuts. I did get a couple of e-mails from folks who drilled out the doubler bar without removing skins. It worked for them. But looking at my project, it wasn't going to work for me. As you approach this, it's more than removing components; you have to easily put them back together again.

As you look at your wing, you'll discover that there's no reasonable way to remove the doubler fork without removing -- or at least getting it out of the way -- the flap brace. It makes the lower rivets inaccessible.

And there's no way to remove the flap brace without removing the flap hinge. So the first step is to remove the rivets holding the bottom skin, the flap brace, and the flap hinge. Let's take a look at proper rivet removal technique.

First, you don't want to make the holes larger or do any damage to parts. Flush head rivets are relatively easy to drill out; it's a two step process -- drill a hole in the rivet head, and snap the rivet head off. How? Simple. And here I call up the expertise of Joe Schumacher of the EAA, who has built something like 19 homebuilt airplanes. You may have seen him on the series "From the Ground Up." He often uttered this piece of advice: "take your time."

Elementary rivet removal. Drill the head in the middle then rock and roll with the end of a drill bit until the rivet snaps off.

There is no better advice for construction of an RV airplane: take your time. And removing rivets requires you to slow down, and be patient. Yes, you have a lot to remove, but in reality you have only one to remove: the next one. So, stay focused on the task at hand and slow down. Some people say you should use a #41 drill to drill off the rivet head, and that's probably wise. But it works easier for me with a #40.

I used an old electric drill because I can turn it slowly more easily than an air drill. Although there is a slight dimple in the head of the rivet, the drill bit is still going to want to run just a bit. So turn the chuck by hand and then slowly begin to drill. Have an old #40 bit standing by. Start the drill, then stop to be sure you're centered on the rivet head. If not, you can apply a little pressure to the drill bit to get it centered. Stop periodically and use the drill end of the spare bit, putting it in the hole. If you can wiggle the rivet head, fine. If not, drill a little bit more until you can.

The temptation here is to rock one way once, the other once and then go for broke and try to snap off the rivet head. That, to me, is where trouble begins. I move the drill bit one way and the other a couple of times and keep doing it until I see the edge of the rivet lift slightly off the dimple in the skin. When I see that, I know that rivet head is a goner pretty soon.

I can't stress enough that impatience here will kill you and you will end up making a bigger problem for yourself. Sure, you can always use an "oops" rivet (you can drill out the hole to 1/8" and use a rivet with a 1/8" shank and a 3/32" head so it blends in), but these are cosmetic more than structural and you don't want to use many of them.

One tip: As you remove rivets over a large area, if you can put a little back pressure on the rivet hole, the head will literally fly off.

Once the head is off, you can use a 3/32" punch and taps on a hammer to push the shank out. However, you must support the other side. A bucking bar or any sort of mass applied against the skin, rib or what have you, will prevent the force of the punch from bending the material. You will need two people for this job because you can't hold a punch, a hammer, and a bucking bar.

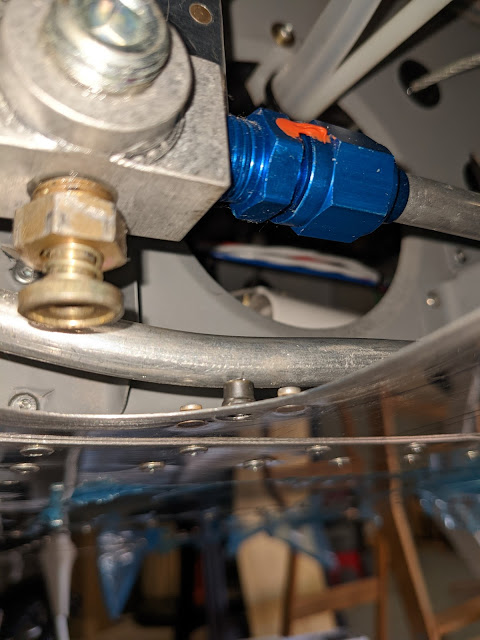

But there is a better way for ribs and things like this. Check out this little item (Photo below) I got from Aircraft Spruce. It's a modified pair of pliers with a punch on one side, and a small plate on the other. The plate provides the backing against the force of the punch when applied by squeezing the pliers. Since there's a hole in the plate where the rivet shank (and shop head) is, it goes flying, your material is left intact. Pricey -- $65 -- but way better than a punch and hammer. Strongly recommended for this job.

Be sure not to hurt the hinge eyes here. You can put some small popsicle stick (you have some left from when you built the wing tanks, right?) spacers on the backing plate of the pliers. Again, take your time.

Remove the entire line of rivets on the flap brace, remove the hinge and put it away somewhere safe.

In order to move the flap brace out of the way, you'll next have to remove the rivets that hold the flap brace on the rear spar. Another task. Another tool. This rivet removal tool (I think I got it from Avery), is perfect for the task. It comes with threaded drill bits and different heads to fit over universal head rivets.

Above Removing the line of rivets that hold the flap brace (and flap hinge) is the first step in making the repair.

This rivet removal tool, used with a drill, is used on universal head rivets. But be careful to get it centered properly.

Now you might think you can just put it on top of a rivet, hit the drill and move on. But you can't. You have to be sure it's centered on the rivet and you have to, again, take your time and be sure the drill bit is centered. With this tool, you can adjust the depth of the drill hole. Same deal here; get it deep enough to allow the other end of an old #30 drill bit to fit in and twist the head off, but not so deep that you're drilling into the spar. Again, be patient in rocking the head before you give it the final effort to pry the head off.

I decided to do this right, and to give me good bucking bar access later, I'd remove the skins, at least all the rivets to the most outboard access hole. You may not want to do this but, again, to me it's a matter of reconstructing things right. Yes, I could try more contortions through the lightening holes in the ribs, but it was my assessment that I couldn't do a perfect job this way and I'd obviously screwed up once and I just wasn't in the mood to try to cut corners here.

So I removed all the rivets along the spar on the skin...and all the rivets on the top spar, and then the rivets on the ribs. Working from inboard out allows you to place very slight pressure when snapping the rivet heads by peeling back the skin as you go.

Why did I take all those rivets out? When it comes time to rivet the new doubler on , I want as much access as I can get. If tried to get away with removing fewer rivets, there was a greater chance I'd put a crimp in the skin, so I decided a little more work would be worth the reward.

With the skin off -- or peeled back -- you'll be able to get access to the underside of the spar, to brace it as you remove the rivet shanks. The neat pliers won't help you here, so to remove the heads, you'll have to use a punch and hammer (there's also, from what someone posted on one of the builder groups), a "punch-like" bit you can put in a rivet gun. But either way, you'll once again have to brace the other side of the work. With a punch and hammer, you'll need two people. With the punch set for a rivet gun, you'll need one. Take your time.

How many of the rivets to remove? Well, certainly all the way to the end of the fork. But in order to move it out of the way enough, I'd keep going. Now, I removed too many. I went to the second rivet after the center rib. But you'll have to remove enough to get some serious "flex" in the brace to get it out of your way.

Once that's done, you're ready to work on the doublers. This is actually pretty easy since you're going to throw these parts away anyway. Try to remove the rivets as described above. But if that doesn't work, use a grinding stone in a Dremel and grind the heads (or the shop head if you originally put them in that way) down just below the doubler (obviously you don't need to go more than a hair into the doubler). Then take a punch and tap the rivet until you see it depress slightly (enough that the outline of the shank is visible).

Whether you try to remove the rivet now or come back later and do them all at the same time is up to you. I compartmentalize my tasks so I snapped all the heads off (or ground them down), before removing them.

After removing the heads, and punching out the shanks, you just have to take up the old fork and doubler and inspect the spar for any damage. If you take your time and work slowly -- take several days if you have to -- it should be fine. Vacuum up the mess and remove all the old shanks from the bottom of the skeleton (another great reason to remove the skin).

|

| The old doubler heads for he scrap heap |

As luck would have it, the day I finished this task, was the same day the new parts arrived. Turning my attention to them, I just used a drill press to enlarge all the holes to #30, and deburred and polished all the edges.

Just for the heck of it, I placed the old doubler on the new one and traced the old hole to see how the edge distance of the new one would work if I didn't do the trimming. Then, I got out Drawing 38 (for an RV-7A), and -- since it's full size -- placed by doubler on the drawing and marked where the trims were to be made as instructed and it is here where I discovered my mistake that got me here in the first place.

Instead of just placing the part on the drawing and marking the locations of the trims. I used the dimensions specified in the drawing to mark the original parts. I got the dimensions right, but my reference was wrong. As you can see in the photograph, instead of marking the inboard trim by drawing a line up the inboard edge and then measuring outboard the required distance, I measured from the top inboard edge. Bad mistake, because if I'd made this part right in the first place, even my misdrilled hole at wing-mating would've been acceptable.

|

If you look closely at the schematic, you can see why my stub ended up too short.

|

I intend to replace the fuselage fork also, but just in case I change my mind and want to use the existing fuselage fork hole as a drill guide into the new part (something I presently think is a bad idea), I marked the dimensions for the trim on the new parts and then made absolutely sure I left an additional 1/32" of material after the cut. I made the cuts, deburred, and polished the edges, and then Alumiprepped, Alodined, and primed the parts.

The next day I clecoed the fork and doubler in place. There's nothing new here; you've done this before. Just take your time. Rivet the lower line of rivets first. The directions call for the same sized rivet (AN470-4-6 as I recall) from the outboard end all the way down to (but not including) the doubler plate...even where the ribs are. If you accidentally enlarged a hole a bit in the rear spar (and, let's face it, you probably will one or two), going one size larger here will work fine. Then do the doubler plate (I used a slightly longer rivet on these too than what the directions called for). Be sure not to rivet the three 470 rivets that connect the flap brace to the doublers. After all the bottom row rivets are completed, cleco to the flap brace back on and do the three inboard rivets.

When you do the top row, Place some duct tape on the edge of the top skin. In fact, you should do this before drilling the old rivets out, too.

What's left now -- mostly -- is the top row. You'll need a partner here because, unlike when you first rivet this part -- there's a top skin here now. And you can't get a rivet set on the rivet head without interfering with the skin. The question isn't whether you'll hurt the skin (although that's a possibility), it's that you'll put some smilies in the rivets.

I admit, I got a few smilies in mine, until I called upstairs and asked my wife to contribute her time to pull on the top skin edge enough to allow me to get the rivet set on straight.

The task is done. That Sharpie writing on the flap brace says "don't forget to put the hinge on."

With that task completed, you're now ready to rivet the rest of the flap-brace-to-rear spar rivets. This task, if you took as many rivets as I did out, is impossible without removing the wing skin. But since I did, I was able to easily -- and quickly -- reinstall the flap brace with mostly perfect rivets.

So ahead. Give that beautiful new doubler a tug. Strong? You bet. And admit it. You feel good about making right one of the worst mistakes in building an RV airplane. I sure did.

Now, it's just a matter of re-riveting on the bottom skin. Work outboard to inboard -- just the opposite of when you installed them. Work forward to aft to forward and you should be able to keep enough of the skin peeled back to allow you to get your arm up through a lightening hole to buck the most aft rivets. The hardest rivets to buck are the same ones that were hard the first time around -- the second and third bays at the bottom along the main spar. I got one bay done OK, and then decided to use pop rivets on ones that I decided I had a good chance of doing damage with if I were to try to buck them.

The last task is the first one in this article -- putting the line of rivets back in that solidifies the bottom skin, the flap brace and the flap hinge. Caution: It's really easy here to forget to put the hinge back on (or have you never riveted a line of stiffeners without the stiffener or a nutplate without the nutplate?).

I also used the occasion to dimple the holes for the wing fairing attach nutplates (and, of course, ordered new nutplates.)

And you're done.

The next step -- for me -- is to evaluate getting at the fuselage fork to replace it. Fortunately, I put screws in on the baggage compartment floor (except along the bulkhead) to get at things underneath there rather than drilling out pop rivets. Just thinking it through, though I can see some real contortions trying to get at that doubler fork. We'll see. I'll update this article later.

Update: I've decided not to replace the fuselage clevis. Here's why. In order to start "completely over" with a new hole, I'd have to replace both the front and back of the fuselage fork. The trouble with that is the most aft part of that fork carries all the way over to the other side and forms the aft end of the left wing fuselage clevis. So that would necessitate removing the rear spar doubler on the other wing too because there would be no way at that time to drill a hole in that clevis and have it perfectly center in a hole that is already drilled in the rear spar doubler on the left wing. To me, it would be stupid to ruin a perfectly fine mating job.

I could also replace just the forward part of the fuselage fork clevis -- that's just a bar with about 6 or 7 rivets (and several bolt holes) in it. That allowed me to drill using the existing hole as a guide.

The third possibility was to do nothing with the fuselage clevis and using the existing hole as a drill guide and figure out a way that the hole in the aft fuselage clevis (already drilled) through the new spar doubler (not yet drilled) mates up perfectly with the hole in the front of the fuselage clevis (already drilled).

Ken Scott's advice: I think the third proposition is the best. My...cousin...didn't have to solve this one, because only the wing portion was a problem. However, if you stick a long rod through the clevis, slip a block with a drilled hole over the rod and clamp it solidly to the fuselage and remove the rod, you will have a drill guide.